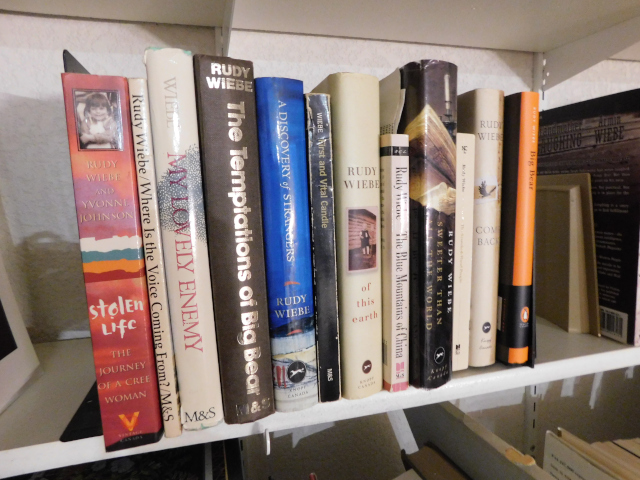

The above photo is one of dozens of photos that I’ve taken of Pyramid Mountain in Jasper, Alberta. It’s so distinctive, and so dominant that even the most desultory of tourists driving through the small mountain town will learn its name and identify it on photos years later.

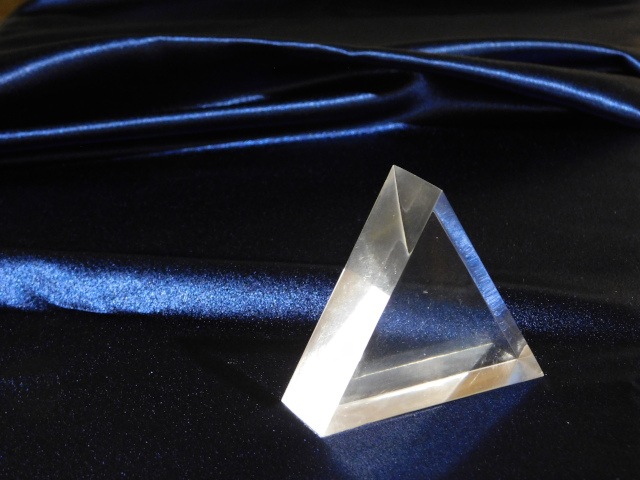

When I arrived in Jasper in the summer of 1968 as a university student hoping to earn next year’s tuition, I was lonely. I’d never lived that far from home before. Pyramid Mt was the first mountain whose name I was given, and I quickly came to think of it as a friend. It was always there – solid and beautiful. I won’t say “unchanging” because a major part of its charm was that it never looked exactly the same. The mountain’s iron-red rock caught the light of the sun, or the moon, from all angles and refracted it into grandeur. I was fascinated anew every time I walked “home” after work to my half of a double bed in a tiny bedroom on the crowded upper floor of an old house (most houses in Jasper had been converted to making as much money as possible in the summer tourist season).

In the decades since living in the magnificent and beneficent presence of Pyramid Mt., I have revisited the town many times. Each time the drive along the Yellowhead Hwy feels like a journey home from the minute I recognize Pyramid’s backside, which is a non-descript gray; only intimate familiarity allows recognition from that angle. As we near the town itself, there is Pyramid, ever reassuring, warm as only stone can be.

The ubiquitous cartoon image of a guru sitting on the top of a mountain, dispensing wisdom, is a modern belittlement of an ancient habit of looking up to the hills for divine guidance. As a familiar line from the Book of the Psalms puts it, “I will lift up my eyes to the hills / From where does my help come?” It is not mere happenstance that we describe a powerful awareness of transcendence as a “mountain-top” experience.

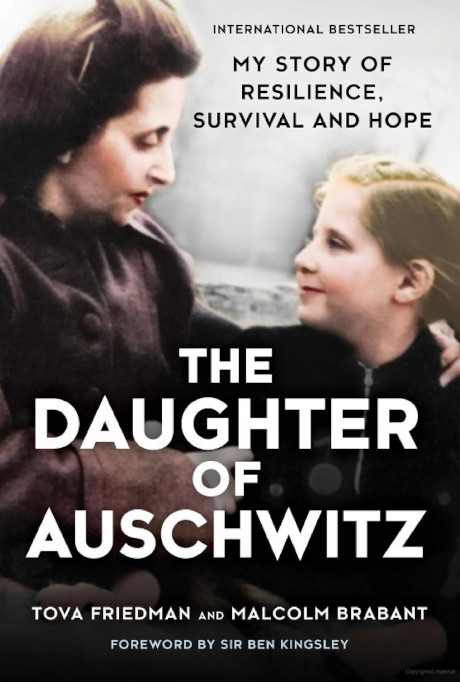

Which came first, I wonder, our experiences of the rarified atmosphere so far above sea level or the influence of powerful myths in various religions that equate mountain tops with divine revelation? Moses did receive the Ten Commandments at the top of Mt. Sinai, and long before that, the ancient Hebrew patriarch Abraham was ordered by Yahweh to take his son up onto a mountain, where he learned a dramatic lesson about trust and about the abomination of human sacrifice.

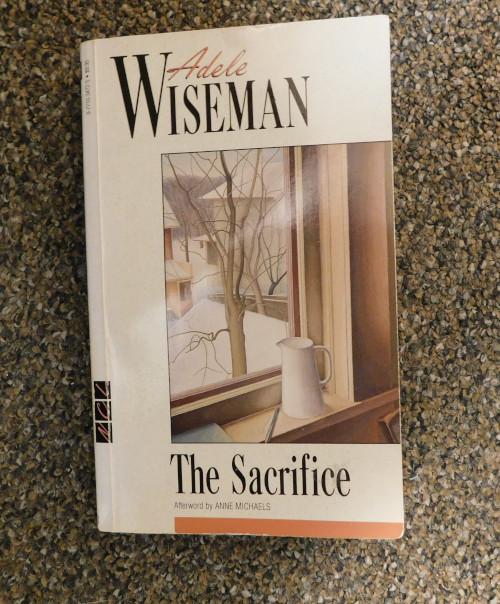

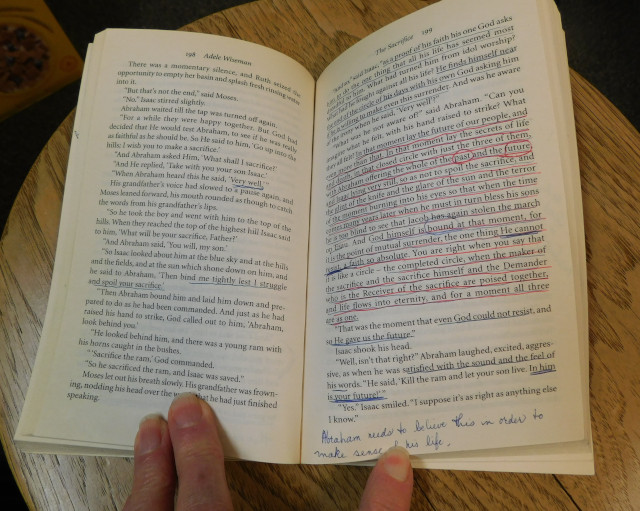

In a disturbing, yet hopeful, reworking of that old story, The Sacrifice by Adele Wiseman invites us to pay attention to our own uses of narratives. When I first read the novel, I was aghast at the tragedy at the heart of it, and even more so after I learned just how utterly taboo it is in Jewish teaching to take a life. The various interpretations of the novel that I read in preparation for teaching the novel left me unsatisfied. All of them seemed baffled by the shocking contradiction between an elderly Jew devoted to Torah and deeply in love with God, and an act of killing for seemingly no discernible reason.

I read and reread, noting the obviously symbolic names of Abraham and Sarah and their son Isaac, not to mention daughter-in-law Ruth and grandson Moses. Echoes of the Book of Genesis were everywhere. The modern Abraham and Sarah and their son are refugees, having fled their country after losing two sons in a pogrom in Europe. To see them settle in a Canadian city and begin to make friends was heartening. Until the story turns deeply troubling.

There is a mountain in that unnamed city where the family chooses to settle. It is not at all like Pyramid Mt., more like a high hill, yet it figures largely in Sarah’s imagination, especially after Isaac’s death. It is a disturbing mountain, perhaps malevolent. On it stands an asylum for the insane. It is not a source of wisdom, nor yet of friendship; it just stands there, hinting at some significance, waiting for its time to offer wisdom out of suffering.

At the end of the novel, grandson Moses, now almost a man, finally ascends the mountain to visit his once-loved grandfather who has been living in the asylum for years. In their awkward conversation, Abraham attempts to reclaim his role as a voice of wisdom, but it is with painful humility that he mutters, “I could have blessed you and left you. I could have loved you.” To whom, wonders Moses, was Abraham speaking? Not seemingly to him, but both blessing and love are offered to him anyway. There is an awakening here of some kind, an enlightenment.

The thought came to me eventually that Abraham’s tragic mistake was in claiming the Biblical story of Abraham as his own, believing that he could control God’s blessing on him and give meaning to his own suffering through reliving the ancient stories. Long before he was guilty of murder, he was guilty of spiritual pride, of grasping that which should have been given, or not, as the case might be.

That thought gave me my first academic paper, which is far less important to me now than the truth that Wiseman explored through her novel: we need to be cautious about the stories that we claim as ours, that we choose to live out—and we do live by stories, whether we recognize them or not. Myths (in the original sense of deep stories that explain humanity’s role in the world) are powerful; they shape us even more than we shape them. It behooves us to ask ourselves frequently: what are the consequences of using this story to give meaning? what kind of person does this story make us? Wayne Booth in The Company We Keep asked it differently, “is this book, this story, the kind of company that is good for me? Who am I when I am with this [book] friend?”

What are the consequences of using this story to give meaning?

What kind of person does this story make us?

The mountain still stands, whether it be a friend or a dangerous other. In my mind, Pyramid Mt. counsels love, for all people, for all of creation.