Writing a blog, which I’ve done for almost four years now, is a lonely affair. I’m not complaining, since writing is almost always a lonely pursuit. Every now and then, though, I do think more particularly about my readers and try to imagine where you might live, or what we might talk about if we could have coffee together someplace interesting–in your country or mine.

Writing about Christmas is an additional challenge because of all the designated holidays that I am familiar with, this one has been written about and sung about and indulged in and celebrated more than any other. Surely everything that can be said about Christmas, concerning whichever grand narrative you choose to focus on, has been said – many times over. A wish list, on the other, can be new every year.

Unfortunately, these days the world seems locked into so many conflicts and stupid flirtations with apocalyptic scenarios that the very act of creating a wish list seems frivolous. One could, of course, go big and like one of my grandchildren, add to the list “the moon.” Why not? Why not ask for the utterly unlikely, such as world peace?

Instead, I will retreat as I often do to the small things, for they matter more than we think: it is out of little actions that our habits of mind are formed, and it is out of our habits of mind that we make the big decisions and the crucial speeches that can change the world. Well, our own small spheres at least.

So, the list:

At least once, in the days before and after Christmas, I wish for you the time to watch an entire sunrise, preferably in a place without street lights and power lines. In my part of the world, the days are very short now, and the sun rises after breakfast, as it were. Take a cup of coffee or cocoa with you and watch the subtle first hints of color transform themselves into a blaze of glory. It is always a miracle, especially when the nights have been long and dark.

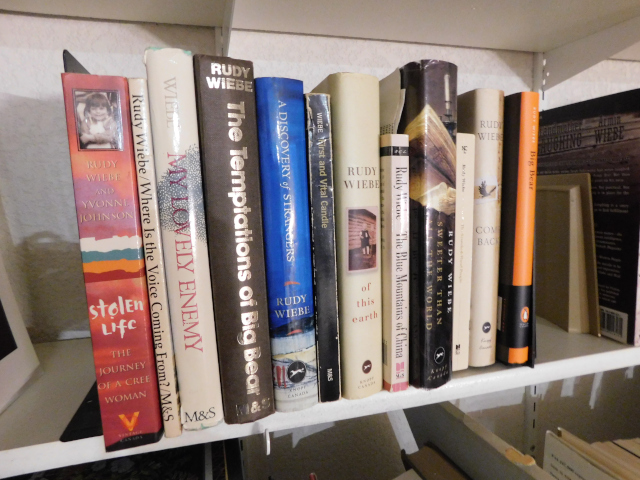

I wish for you two uninterrupted hours or more in which to curl up in a comfy chair or wide window seat where you can let yourself become utterly absorbed in a good novel. Preferably a classic or a young adult book that will bring you into a world that has a stable moral centre and in which a happy ending can be anticipated.

I wish for you many warm hugs and I-love-you’s. There might be gifts involved as well, but they aren’t that necessary, are they?

I hope that in your home, your office, your favorite hang-out, there are flowering plants. In my world, that’s most likely to be poinsettias, but maybe you’ll be lucky enough to be near a spectacular amaryllis in full bloom. Or maybe where you live, there are gorgeous flowering shrubs outdoors. Let there be someplace where you can smell the earth and savor the complexity of petals with their heavenly tints.

And this last wish might seem perverse or more like an admonition than a wish: I hope that there is at least one opportunity for a phone call or an in-person meeting in which you can say, “I’m sorry,” and be heard and still feel safe. We are none of us faultless. Without a doubt, there are individuals who need to hear an apology that will open up possibilities for better understanding. Christmas inevitably contains some tough stuff; it’s the fall-out, I suspect, from over-wrought expectations of all sorts. I wish for you one interval of time, however brief, in which hope can arise and love increase.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!