The last academic conference that I attended—Congress of Social Sciences and Humanities 2011—was held at the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB. My husband had traveled with me this time, a few days before the conference began, so we could have a short holiday before I settled in to listen to many academics demonstrate their prowess with words and ideas.

We visited the Hopewell Rocks, which we had been told many times we “absolutely had to see.” For land-locked prairie dwellers whose typical holiday was hiking in the Rockies, the mud flats of low tide, stretching endlessly toward the sky, were astonishing all on their own, never mind the mud-and-rock sculptures shaped by the tide, in its back-and-forthing for millenia. They were huge; they were grotesque and majestic all at the same time. Some were named: “Bear,” “Elephant,” “Dinosaur.” We were awed almost as much by the vast quantities of seaweed heaped up and sprawled everywhere. The mud itself had an enticing silky smoothness; I wanted to keep touching it.

Eventually, exhausted by sensory overload, we sat down on a clean rock to have some lunch. My gaze shifted down and inward. There is rest in mindful attention to detail. I had begun to appreciate still life photography, thanks to regular visits to Shawna Lemay’s blog Calm Things, which preceded her current blog Transactions with Beauty. I was learning to delight in small things, calm things, gentle juxtapositions, artful compositions. I was beginning to notice shades of color, textures, and lines, sometimes as subtle and beautiful and complex as anything I traced through novels and poems in my classrooms. So here, on a smooth rock in the midst of the ungainly, preposterous Hopewell Rocks, I assembled one small rock and half a kiwi, next to the line through which life was persistently growing.

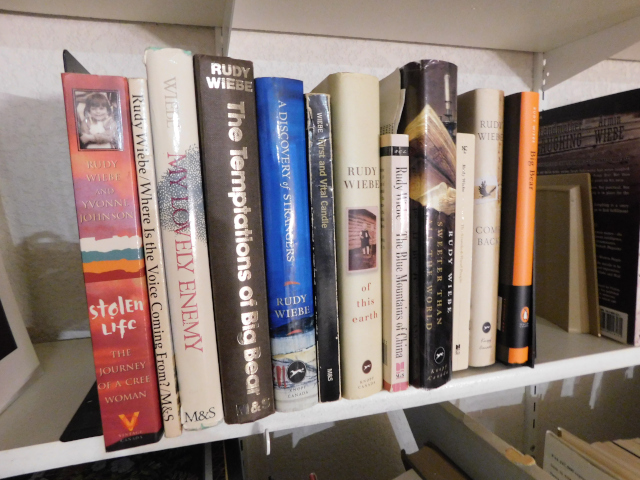

My interest in Mennonite literature, which eventually became my PhD dissertation, began back in the early 1960s when I was in high school, when our small town’s comfortable insularity and piety was disturbed by the grandfather of Canadian Mennonite literature, Rudy Wiebe. His first novel (begun as an MA thesis) Peace Shall Destroy Many (1962) was the first novel in English by a Mennonite writer, and its realistic presentation of Mennonite life, with its hard work, godliness, pacifism, prejudice, and hypocrisy caused consternation among Mennonite congregations across Canada. That’s by way of backstory.

Wiebe subsequently became a major figure in Canadian literature; his best-known novels—Wiebe earned his first Governor General’s Award for fiction with The Temptations of Big Bear 1973—concern Indigenous peoples. He also wrote several novels with Mennonite characters at the centre, the last of which is Sweeter Than All the World (2001).

It was vintage Rudy Wiebe: a cast of unforgettable characters that spanned the entire history of Mennonites beginning in the 1500s; a central character struggling to make sense of his personal history and his inherited theology; a demanding, thick and powerful prose style that packed clauses within clauses in a breathless avalanche of thought and sensation, thus demanding close attention and several rereadings; and a network of metaphors that knit together not only various plot elements and characters in Sweeter Than All the World but also key themes explored in his previous Mennonite novels. I became aware of those latter connections only as I was working on a conference paper on STAW. As I unravelled and rewove those intertwined images, my heart strings were tugged so often that my writing repeatedly snagged to a halt in the midst of family memories of my own. Our worlds are not that far apart; his Mennonite novels lay bare my world, too.

Sweeter Than All the World may be difficult for non-Mennonites to get through. It takes a certain kind of awareness of both community solidarity and shared family histories of broken family connections to persevere through Wiebe’s seemingly fragmented story lines, so filled with suffering and loss. In the end, though, the fragmentation is undone, as much as it can ever be, by lines: threads of continuity, melodic lines of song, genealogical cords, pulleys and cables, all bound together by crucial sticking points (both those that hold—needles and poles—and those that hurt—knives), seemingly rooted in the earth. Call it grounded community, if you will, unsentimental, essential.

Fiction lets us enter other worlds, try on other identities, evaluate other values. It is thus that we learn compassion – through narrative imagination. Sometimes, too, fiction lets us see ourselves from another angle, from which we can test the strength of our personal connecting lines that let us grow.