In a world in which nearly every imaginary activity has been gamified and even “gaming” became a necessary new noun, I’m going to dare to write about old-fashioned board games. Yes, those games that come in cardboard boxes and are laid out on the table for the family to play, using dice and cards and little plastic people. What an anachronistic activity! Oddly enough, though, board games are still popular, if one can judge by the seasonal pop-up kiosks in shopping malls selling paper calendars (another anachronism!) and board games, both old and new. Apparently, the artifice of moving pieces on a board still holds some appeal.

It was by happenstance that my husband and I discovered we had not fully understood either the rules or principles of Ticket to Ride, a discovery that changed my feelings about the game to a degree that I found disturbing. I’d never really paid attention to why I liked some games and disliked others. Now I needed to figure out what had really changed in my attitude to Ticket to Ride and if that mattered in any way. It wasn’t just an objection to a seeming rule change; given how freely we had adjusted the rules of Brazilian Rummy to make it more playable for just two people, I clearly did not feel that rules were immutable.

When attitudes and behaviors seem inexplicable or downright weird, it usually pays to look back as far as necessary to work out what’s going on. In this case, that meant saying “hello” once again to my childhood self, that shy little country girl with minimal social skills.

In my family of origin, games were played only on Sundays when work was not allowed. Often those game-playing sessions were enhanced with home-grown, freshly roasted sunflower seeds or still warm popcorn. These are some of my happiest memories of farm life, albeit not without shadows.

I was the youngest in the family, by a margin of 6 years, so games that required strategy or skill were impossible for me to win, unless someone let me win, which, I realized fairly early, was an insult of its own. So unless some element of randomness was built into the game, I wasn’t particularly interested.

Strategy vs. chance: surely the makers of games have always grasped that much depends on the balance between those two. There were those in my family who definitely preferred checkers and chess, especially the latter. Both players begin with identical playing fields and number of pieces to march toward victory. The board is a battlefield that is level in all senses, and all possible moves are clearly delineated and equally available. There are no dice and no cards. Checkers and chess are games of intelligence only. There is some built-in aggression (the third key factor in games), since pieces are mowed down along the way. However, each assault on the opponent’s troops carries definite risk to one’s own. There is little tactical benefit in “killing” for the sake of “killing.”

My father, I recall, never played Snakes and Ladders, which is entirely chance: the roll of the dice determines everything. (The moralistic notes on the board that connected ladders with good behavior and snakes with naughtiness were completely negated by the way the game was actually played. One can’t help but think of the way that good behavior has become suicidal in politics these days and naughtiness simply extends influence and power).

He also had little patience with Sorry (which I really liked) because while there were some limited choices, so much was determined by the luck of the draw that there was little pride in winning. Possibly my father had had more than enough randomness in life (he had come to Canada as a refugee) that he did not willingly tolerate chanciness. Not that he was averse to risk, per se; he just wanted as much control over the degree of risk as possible.

Monopoly was another game that we often played; it did include some randomness—players roll the dice for every move. Mostly, though, it depended on economic strategy. It was capitalism in miniature. And I do not recall ever winning a game. Monopoly’s one virtue was that it didn’t lend itself to open aggression among players; winning didn’t depend on deliberately sabotaging someone else’s opportunity to make money, except by capitalism’s inherent principle of taking advantage of an opponent’s fiscal distress.

Interestingly, I recall laughter accompanying Monopoly, at least in the early stages of the game before the bankruptcies began. There was laughter with Sorry and Pit and Crokinole and other vintage games. There was no laughter at the chess games. Intellectual ability was on the line, and intellectual prowess was highly valued.

So, back to Ticket to Ride.

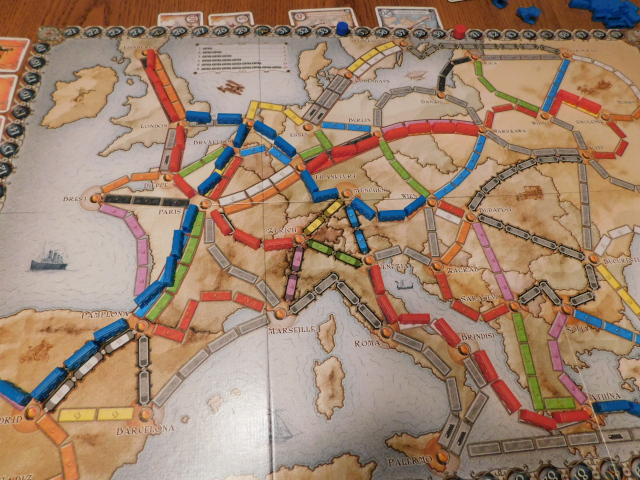

We had not figured out that the game was designed, not only to require strategy (every turn involves some choices), but also to reward sabotage of other players. Suddenly, the game felt less benign. My husband and I had enjoyed the game so much, I think, because it required us to think carefully and to work with whatever cards we were dealt (that element of chance), but left the inevitable interferences with one another’s trains also to chance: skill plus chance in a ratio that minimized the importance of winning or losing. There was little personal pride at stake: it was the process that was fun.

We have watched our children and our grandchildren play board games – and we played with them, of course. As any elementary school teacher could have told us, not every child can handle the competitiveness fostered by games that depend on aggression as part of the winning strategy. One game, rarely played by our children and played only once by grandchildren, was actually named Aggravation. The entire point of the game was to be mean to your opponents. Granted, there was a substantial element of chance in the game, but not enough to neutralize its corrosive effect.

It has been fascinating to observe a new trend in board games: cooperative play. The competitive element has been eliminated and players are all on the same team, facing the challenge posed by the game itself, each contributing some skill to the communal effort. I have not played such games enough to speculate on what has happened to the role of chance in these new games. No doubt much research on precisely that element has already gone into their design.

For now, my brief visit to the past has not only helped me to make peace with Ticket to Ride—as long as we can “adjust” rules to suit us, there’s no problem—but has also ended my sentimental attachment to the now very old board games that still sit on our library shelves. The time has come, I think, to dispose of some ancient paper money and some deteriorating game boards. I hope that I can find some recipient for the antique wooden chess pieces, since it seems a shame to consign those to the garbage.

What I should consign to whatever dustbin holds mental behavior patterns is my competitive desire to win at games, however chancy they might be. I hereby admit that I have never been immune to the allure of beating the odds. After all, my pride is at stake.