I had a friend.

The past tense is like a knife in the heart. Not the kind of ragged-edged knife of a friendship fallen apart for reasons that could have been avoided had we each made some effort. No, not that kind of knife. Such jaggedness could not have happened between us. It is instead the apartness of finality and inevitability – Death wielded the knife.

Our friendship began when we were both past the life stages in which bosom friendships usually take root. She was older than I, by a decade, and already retired. Normally those are years in which old friendships (those that have survived) are tenderly nurtured, while newer friendships hover just past the level of acquaintance. It is not easy to build a solid relationship when so much of life has already become memory. Yet within months of our first meetings in the context of a church which both of us had newly joined, we were meeting for long, animated breakfasts, hearing each other’s history for the first time, learning the names of family members we’d probably never meet.

Part of the joy of growing this new friendship was the repeated surprise of discovering strange commonalities. None of my previous and current friends had listened to stones speak (sometimes bringing them home). We both appreciated art, although her taste was more whimsical and eclectic than mine; it was enough for us to recognize in one another a similar eye for the line that seemed initially “off,” the color or shape that surprised, the slant of light that provoked thought.

While our ethnic origins were totally different—I had only recently learned that there was this whole other kind of Mennonite who had never heard of Wurst and Kielkje—we shared a deep interest in Mennonite history as well as an aversion to the pietism that had changed Anabaptist principles into evangelicalism in many branches of the multi-limbed Mennonite family tree. She’d grown up with that aversion; I had acquired it in the recent decades.

Our family dynamics, both past and present, were very different. Our reading choices overlapped barely half of the time. Yet we met happily in small coffee shops and restaurants, in each other’s backyards, and once in very early spring at Saskatoon’s Forestry Farm to huddle in warm jackets and share a thermos of coffee, just glad to be outdoors. We met also in church committees (good ones and challenging ones), and we knew one another as kindred spirits. We both loved fruit, loved picking berries, loved gardening. We both delighted in dance, a joy she had had all of her life while I’d had to begin learning in my 50s, stubbornly undoing decades of misguided forbiddings that she could scarcely comprehend.

In her presence, I learned to think about spiritual geography and understood that souls breathe freely in different spaces: I sense the Divine Presence in mountain scenes, the higher the better; she needed wide-open prairies. I cower in the presence of wind—it is alien to me; she smiled with acceptance and possibly a recognition of kinship.

These days her non-presence is everywhere. I look at an ailing wee plant and wonder if she knows how to make it live well, before recalling that I can’t ask her that. I read a delightful poem about gardening and think, “I’ll send that to her,” only to remember that I can’t. Where she is now is beyond email reach. Someone asks me a difficult question and her words slip from my lips, “I’ll have to think harder about that.”

Although she never identified herself as a writer, as I do, she knew the power of language. She had always loved words and wielded them with care. Like me, she had kept journals; unlike me, she could separate herself from her written processing of pain and simply destroy what was no longer necessary. She could choose art (paintings, music, poetry, pottery) that nourished her without becoming a collector. There was a minimalist elegance in her home that was warm, not chilly. A guest belonged instantly and felt at ease.

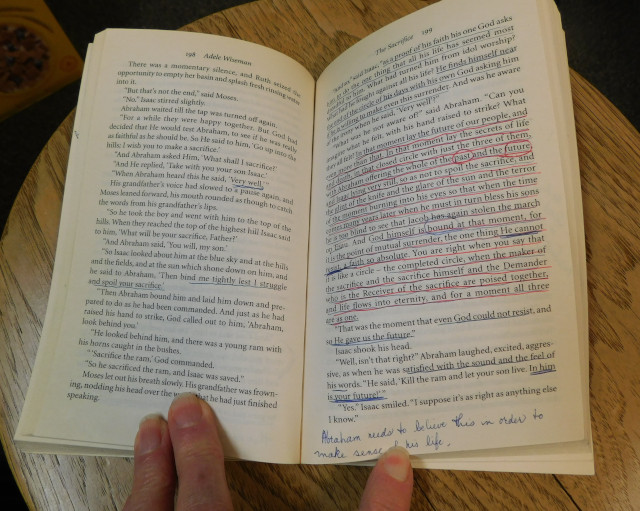

For many years, she functioned for me as a kind of intuitive editor. Well, she said she was no editor, didn’t know how to do that work. Despite that, I often sent her drafts, sometimes with specific questions about something I knew was off, sometimes with no instructions at all except “please read this.” This blog has come about partly through her encouragement and many a posting has gone to her email inbox before it ever became public. Some times I rejected her suggestions (she didn’t like my stylistic experiments), but more often than not, my writing benefited from her tentative “that paragraph didn’t quite work for me.” I shall always be grateful for those conversations.

Was she a perfect friend? Of course not. No such entity exists. She would have been the first person to insist that she had flaws, weaknesses. It is strange that we did not agree on what those weaknesses were, at least not often. Is that not what friends are for? to tell us that to which we otherwise remain blind? She was my wise woman friend, yet ironically, her final gift to me has been to point out, by omission, what processes of good-bye are essential.

I shall light some farewell candles with other people, despite your prohibition, my friend, because grief in solitude and in private is a stifled grief. I shall bring flowers to share with others who were blessed by your presence because flowers matter to the living, not the dead.

And I hereby offer these words to the world in your memory.